This one is gonna work a little differently. This is gonna be one of those Theory articles. We’re still talking about a piece of art, but since we’re not playing it, we need to change the formula up a bit

What’s the intent?

Why was this made? What is it trying to tell us? What intentions exist beyond the tautological one – that it exists to be played.

We experience games as art

This one’s the same, but we’re doing a different conclusion. We are no longer responding to the emotional artifact of play, we’re interrogating this art. What does it mean for the medium as a whole, and why is it important?

The Lost Universe is a Dungeons and Dragons adventure published by the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. It was designed by Christina Mitchell, with graphic design by Michelle Belleville, and development and editing by Kenneth Carpenter, Katy Cawdrey, Rob Garner, Karl Hille, Peter Jacobs, Jim Jeletic, Esben Jepsen, Paul Morris, Gage Taylor, Elizabeth Tammi, and Lauren Ward.

I’m going to be up front – I did not play this game. I am not interested in the play it seeks to create. But I am interested in the artifact itself – why was this made? For who? And all the other ttrpg stuff it made me think about.

What’s the Intent

The Lost Universe takes place in the magical realm of planet Earth. You play as a collection of NASA researchers who are mind swapped1 to the fantastical realm of Exlaris; a rogue planet – one that travels aimlessly through empty space. This isekai cum Shadow Out of Time is a little unorthodox, you have swapped minds with inhabitants of the planet but you still inherit their fantasy and racial2 abilities. The reason for your soul kidnapping is to correct a similar interdimensional swap3. A green dragon on Exlaris has used the same magic to steal the Hubble telescope, retroactively erasing its existence from the Earth timeline.

There is not much to this adventure. I don’t mean that as a slight. It’s designed for a one-shot as a way to get kids interested in astronomy by means of a popular pastime. You show up, you talk with a few characters, perhaps aligning with a faction. You head out into some ruins, you dodge a trap, you fight the boss, and you win. But we’re not here to talk about a stereotypical dungeon crawl. We’re not even here to talk about the gamification of education4. We’re here to look at the peculiarities of this adventure. The ways it hews to and from the hackneyed premises of this artform. Glean some informative from this piece of art created by an alphabet agency of the United States government5.

The centrality of NASA is the body this art orbits. I won’t belabor an explanation of NASA, you can read about that at your local library. This is the United States’ hope bucket. The well from which we draw our imaginations of the most honorable national pastime – space travel. An organization that, for being an agent of Western Empire, is supposed to be the positivist, egalitarian, optimistic future crafter. What does a fantasy world, an entire world wrought from imagination, look like to NASA?

It’s a rogue planet inhabited with life. Mages used dark energy (the real concept) to craft an artificial atmosphere. This magic is also used to power thel lights that serve both as sun and protective wall. When Exlaris was separated from its solar system all the monsters that lived underground emerged onto and settled the unlit surface.

Exlaris is a geniocracy, a society ruled by scholars. Or at least, that’s what the adventure tells you. It tells you a lot of things. What it shows you is somewhat different. The mages have sealed knowledge of dark energy away. It is explained this was done in order to protect the artificial atmosphere, as hurtling through space has granted access to far greater amounts of dark energy than in orbit. Energy that may be harnessed for nefarious means.

The adventure claims Exlaris is guided by the values of peace, open information, and astronomy. It is also a world with five major cities that maintain trade through teleportation instead of roads (because of all the monsters). It’s unclear what portion of the planet has been abandoned to perpetual night or how much of the population was lost in this apocalyptic scenario. It’s also unclear why the city the adventure takes place in, a city that prides itself on peace and freedom of information, has secret police6.

This is perhaps the most classic DnDism of all of The Lost Universe. A direct genetic lineage of the ur-text, Keep on the Borderlands. There are always cities. Bastions of civilization besought on all sides by monstrous, evil hordes. These cities are always, always, populated by hordes of police. How many? How strong? How well equipped? Always slightly greater than the player characters’ abilities.

This is the reality of adventures. This is the raw imaginative material of the American agent, the free-thinking capitalist, the (flashlight under face) liberal. No matter how free you are told you are, even in the realm of complete imaginative fiction, there is no trust. The mage-scholar rulers of this world guard their knowledge lest it be used for wrongdoing (this whole adventure exists because the knowledge, despite the safeguarding, was used for wrongdoing). This free society is maintained by a protective wall. An artificial safeguard powered by energy you are not privy to, maintained by people you are told are the smartest and best fit to rule. We are told this energy is bountiful and yet it is never explained why this artificial light is not used to reclaim the blackened world. Or why these bastions of safety and knowledge need an extensive police force. We are even informed that the loss of five researchers, of five rulers, is enough disruption to cause widespread unrest.

Let’s talk about the untamed wilds. The lands of perpetual darkness inhabited by unnamed monsters. Once players venture into the darkness to seek the Hubble MacGuffin, they encounter zero monsters. They are shown signs they exist, but, in the literal text of the adventure, “travel to this point is uneventful.” You know what is eventful? That’s right dear reader; the dungeon.

The dungeon of this adventure is an abandoned prison. A dragon, our villain, has stolen the Hubble telescope and kidnapped five mages to operate it. Their goal? Typical villain fair. Use the MacGuffin to gain knowledge (power), and hoard it in draconic fashion7. Their lair is defended by an illusion and arrow trap. Don’t ask why this prison has an arrow trap, it’s no longer a building, a thing with context in the world, it’s a Dungeon. A dangerous place with dangerous things to keep people from stealing its wealth. Maybe if our villain employed some of the cops she’d have a better time guarding it.

Once the villain is defeated, the mages saved, and the telescope recovered you are given a choice. The players may be returned to their own planet or stay on Exlaris. If they choose to return, they are detailed with the boundless mysteries of space and the optimistic future to be paved using the Hubble Telescope. If they stay behind, well, they stay behind. The writing is short on details about our new permanent residents, even less so on the unfortunate being whose body they’ve stolen, wandering disoriented on an unfamiliar planet.

We experience games as art

The Lost Universe is a curious piece of art. Its effectiveness at achieving its goals is not in question. It has a decent hook, it’s informative, and then it wraps up. It’s placement within genre tropes is what I find worthy of all this writing. Why is this NASA propaganda told through Dungeons and Dragons?

The answer is straightforward (initially); Dungeons and Dragons is popular so NASA connects with people through the popular thing. Would the message have been more appropriate, more immersively coherent, through the lens of any of the sci-fi ttrpgs that exist? Probably. But then they couldn’t guarantee that any kid in any basement could pick it up and absorb it. Short of delivering it in person8, there is no easier way to populate the imagination of the American child.

The use of DnD is perhaps a more fitting match than the writers expected9. The traditions, systems, and culture of DnD is perfect to accustom the imagination to its rank positivism, complacency, and liberal order. Go out there and do the bidding of the state. Don’t think about what the state enforces, or how it came to be, or how it maintains itself. Someone out there is consolidating power outside of the bountiful generosity of the state and you need to stop them. How come the police network can’t deal with it? And deny you your fun?

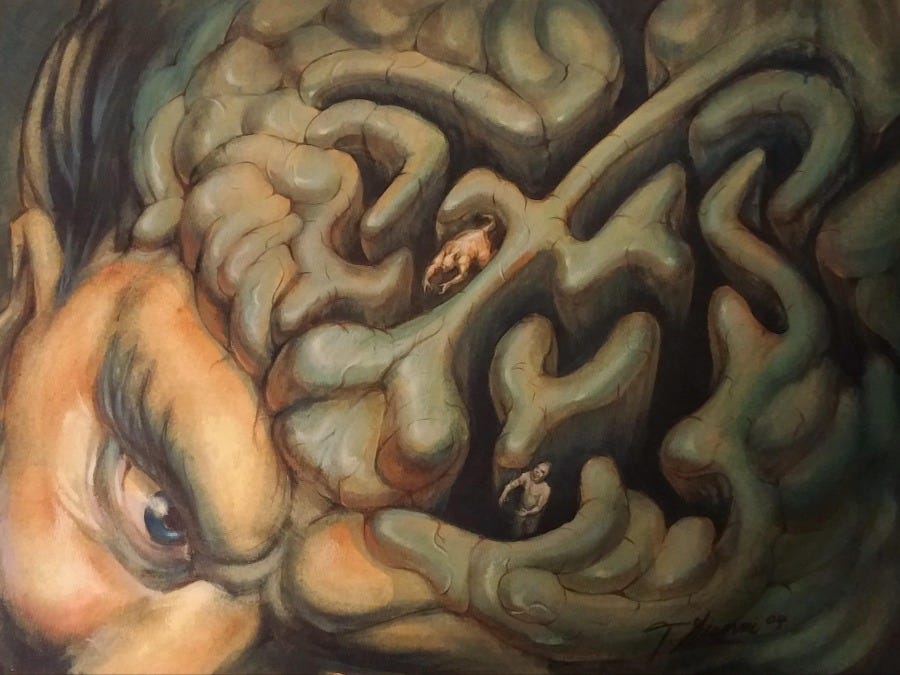

The subtlety of it, of all of Dungeons and Dragons, of the Dungeon is it never forces you to do anything. But it does condition you. It takes the boundless realm of your imagination and puts it in a little maze. Builds walls and traps and monsters around it and then gives you the cheese when you run around inside the walls. It throws a bunch of real and fantasy jargon at you and assumes you’ll accept all of it. It tells you about peace, about freedom of knowledge, about monsters, but it never shows it to you.

Am I calling the very concept of dungeon delving evil? Of playing make believe grave robbing an inherently base and dehumanizing endeavor? No10. It’s fiction. It’s not more real than blasting the bad guy in a videogame or watching sex and violence on TV. But it is a little bit sinister the way it doesn’t ask anything of you. Instead of making us a think whether we are building the kind of fantasy we want, one that it meaningful, we’re already onto the next level and the next monster and pilfering the next golden idol. This entire overarching premise, of getting people interested in science and astronomy and building fantastic machines that enhance our knowledge as a species, and it hands us a sword, points at the monster, tells us it took something from the state, and to take it back with violence.

It’s not as ideologically fetid as the typical dungeon delving scenarios, but it is gross. It has a slimy texture. We are so far into Dungeons and Dragons’ life, it really is unacceptable how closely it still hews to its racial categorization, its imperialism, its eugenics, its dungeon-brained ideology. It taints the optimism, the talk of peace and freedom and knowledge of NASA that it chooses to spread its message by presenting a scenario in which you are stolen from your home, told to pick up a weapon, and conquer or else Earth is doomed to a future without a technological achievement like the Hubble telescope. Because if NASA never built it, no one else would have. If NASA isn’t the one using it, no one else will do the right thing. If you’re not running through those dungeons, then their wealth is as good as gone. Does this make you feel like a hero? Acting as ideological mercenary for a state you’re given no choice in being a part of? One that can abandon you to the darkness, to the monsters, if you don’t go out there and bash those monsters’ skulls11?

Conclusion

It would be easy and self-righteous to end this article with some call to knock down the dungeon walls or something. But that doesn’t feel right. The walls were always fake. Fake in that way all walls are. Instead, I’m going to ask you to be conscious of them. To stop for a moment and look around your brain dungeon. Do you like the structure? Does it make you feel good, the things you imagine? Does this stuff, these adventures, feel like you’re imagining a better world? Or even a fun one? Because if it isn’t, you don’t have to imagine those halls. You can imagine something better. Because when you don’t build the dungeon yourself, you let someone imagine it for you.

HP Lovecraft eat your heart out

Sigh

Isaac Asimov eat your heart out

Although we probably should

Written while holding a flashlight under my face

Yes we are doing this

This might remind you of some mages described earlier in the adventure. This connection is not lampshaded or alluded to by the writers.

Perhaps the Pinkertons could deliver it

At least, I hope it was unintentional. Otherwise this is quite the accusation coming up

Ok, I am a little bit

We’re still talking about Exlaris right?

I enjoyed your thoughts in this piece. Came from twitter to read it. When we are playing TTRPGs, we are often going through the motions of the game. Most will definitely kill and pillage a goblin or kobold's home for the reward of coin from the local townsguard or whomever. The complacency of being an agent of violence used by more politically powerful characters is an easily forgotten trope of fantasy gaming because it seems pretty par for the course and rather normal. I feel that is part of it, but also the social contract of kind of following what the DM has for the players that day.

None of these typical motions make me feel like I am the hero or man I want to be. I only feel like I am an agent of my desires, which happens to align with what other want done in the world of make-believe. I fight, kill, and die to make sure the balance of the world is maintained and evil is thwarted, but I don't feel like a hero. Why is is that? I feel as though I was paid to do a job. Someone needed to die, and my abilities can make that happen. So, I also enjoy your conclusion and it's positive remarks to stay aware of how to better the game you and create and play in.